This week Nicky Haslam’s Folly de Grandeur was published. It’s the story of the house in which he has lived for over thirty years, told in a prose which is never purple but ever so slightly lilac. He writes in the same distinctive, confidential tone that he would use if he were leading you through its pretty rooms himself. There are hundreds of glorious pictures drawing you back to leaf through its pages again and again and their edges are burnished a bright silver.

Nicky Haslam is an English interior designer, old Etonian and cabaret singer, member of the Traveller’s Club, writer and witty columnist, the most beautiful, best dressed and favourite friend and guest wherever he goes. His company is NH Design and its style, like his, is never boring.

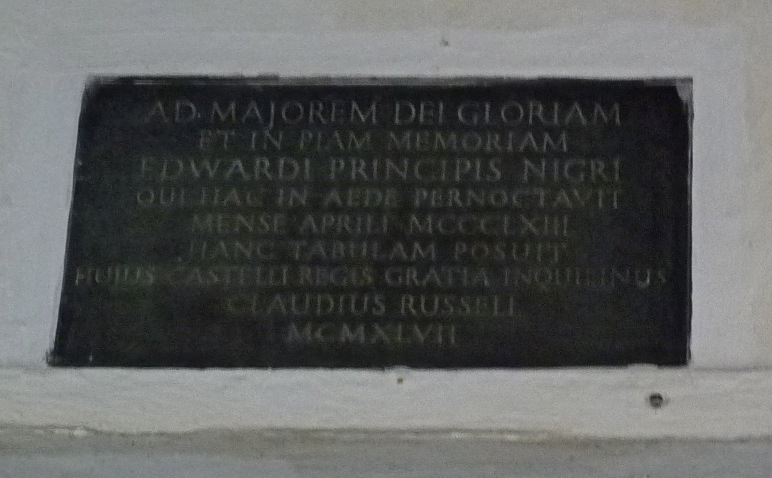

In his autobiography Redeeming Features (2009,) Nicky writes, It is risky to eulogise one’s own home but to me the Hunting Lodge is quite simply the prettiest small house in the world. It was once a Tudor hunting box in the Royal Forest that stretched from Windsor to Winchester. There is a tradition that Prince Arthur the soon-to-die son and heir of Henry VII, first set eyes on his bride Catherine of Aragon there. Nicky has given it the treatment it deserves, with chintz covers gay with roses and fuschia, old pictures and furniture, books, generous hospitality and masses and masses of English flowers from his cutting garden.

These hastily taken photos are not as good as they should be whereas the lunch which came first, one warm summer Sunday, was heavenly.

It was such a good lunch that a few rooms somehow got missed out altogether, including the silvery green Dining Room created by Nicky with its foliate walls painted to resemble an Anglo-Chinese wallpaper and the garden room with one of the most beautiful English Rococo chimney pieces ever. But then these pictures are only an amuse bouche.

Folly de Grandeur will show you all this and much more.

The brick facade is ‘pretend Jacobean,’ put on in the 1720s for the Mildmay family of Dogmersfield Park. Its chalky look comes from the whitewash applied in the nineteenth century and then taken off again. NH points out the vista down to the lake to lunch guest Miss G.K.M.W.

The legendary interior designer John Fowler, a partner in the firm of Colefax and Fowler, found the Hunting Lodge and beautified it in the 1940s, adding an entrance hall and kitchen and reclaiming the garden from heathland. He laid it out in an eighteenth century Dutch style as a very grand cottage garden with many hedged compartments. He lived here until the 1970s. ‘The contrast of discomfort and luxury was an integral part of staying there during his later years’ his friend John Cornforth remembered. Fowler left it to the National Trust and for a while nobody wanted it. Nicky was its next incumbent.

The little entrance hall, added by Fowler and refurbished by Nicky Haslam. French decorative touches abound and the pedestal is in the style of those at Sanssouci, the summer place of Frederick the Great, King of Prussia.

In the long narrow old hall which runs the length of the house, John Fowler had a rather strict and chilly dining arrangement with a round Regency table pushed into one corner. Now it is a place for taking off boots and winter drinks, with a sofa before the fire and huge club fender.

On the marble topped table the etching After Chardin by Lucian Freud inscribed ‘To Nicky,’ sits next to a self portrait by Cecil Beaton. The cire perdue landscape was a gift from Hockney, behind is a huge floor plan by James Wyatt for The Waterloo Palace, in front is the visitor’s book. Signatures from its thickly inscribed pages are reproduced on the end papers of Folly de Grandeur.

The three windows were curtained with Colefax and Fowler’s ‘Oak Leaf’ pattern, now out of production. Lady Homayoun Renwick gave NH enough to remake them to Fowler’s scheme, and he kindly spared me the bit I needed to patch an old sofa cover cover made from the same glazed chintz.

Nicky’s mother Diana Ponsonby, by whom he is descended from the earls of Bessborough, enshrined above the drinks tray. His last big party was held in their former villa Parksted House built by William Chambers on the edge of Richmond Park, where he installed a huge circular rotating dance floor for one night only. The paper in the Staircase Hall is a giant Mauny papier peint flower print which continues up the stairs, Fowler’s choice, restored by NH.

The needlework petit point cover on the low bench was worked by NH. It is a stylised representation of the house’s gabled skyline which took ages to complete. The guest-rumpled French linen cushions are edged with a deep wool and metal thread fringe.

The grand carved wood Baroque fire surround was put in by John Fowler. The lobsters were once part of a table setting designed for Cartier.

The mantle is crowded with invitations and the photographs of friends of the bosom, although in Folly de Grandeur you will see it more formally arrayed with specimen roses from the garden in crystal vases. The painting of St. Francis of Copertino, the patron saint of aviation, belonged to NH’s father.

The busts of a French nobleman wearing the Order of the Golden Fleece, on the ‘David’ table in homage to to the late David Hicks, inventor of the ‘tablescape’ and the giver of several items seen here. NH’s tablescapes are far more generous, running up to and almost over the edges.

The master bedroom with its canopied bed (not seen) and blue grey dragged paintwork divided with wallpaper border strips of a Mauny design.

The garden room contains its own complement of books, pictures, pretty china, sofas, drinks and a huge fireplace. There is a potting shed orneé at the rear.